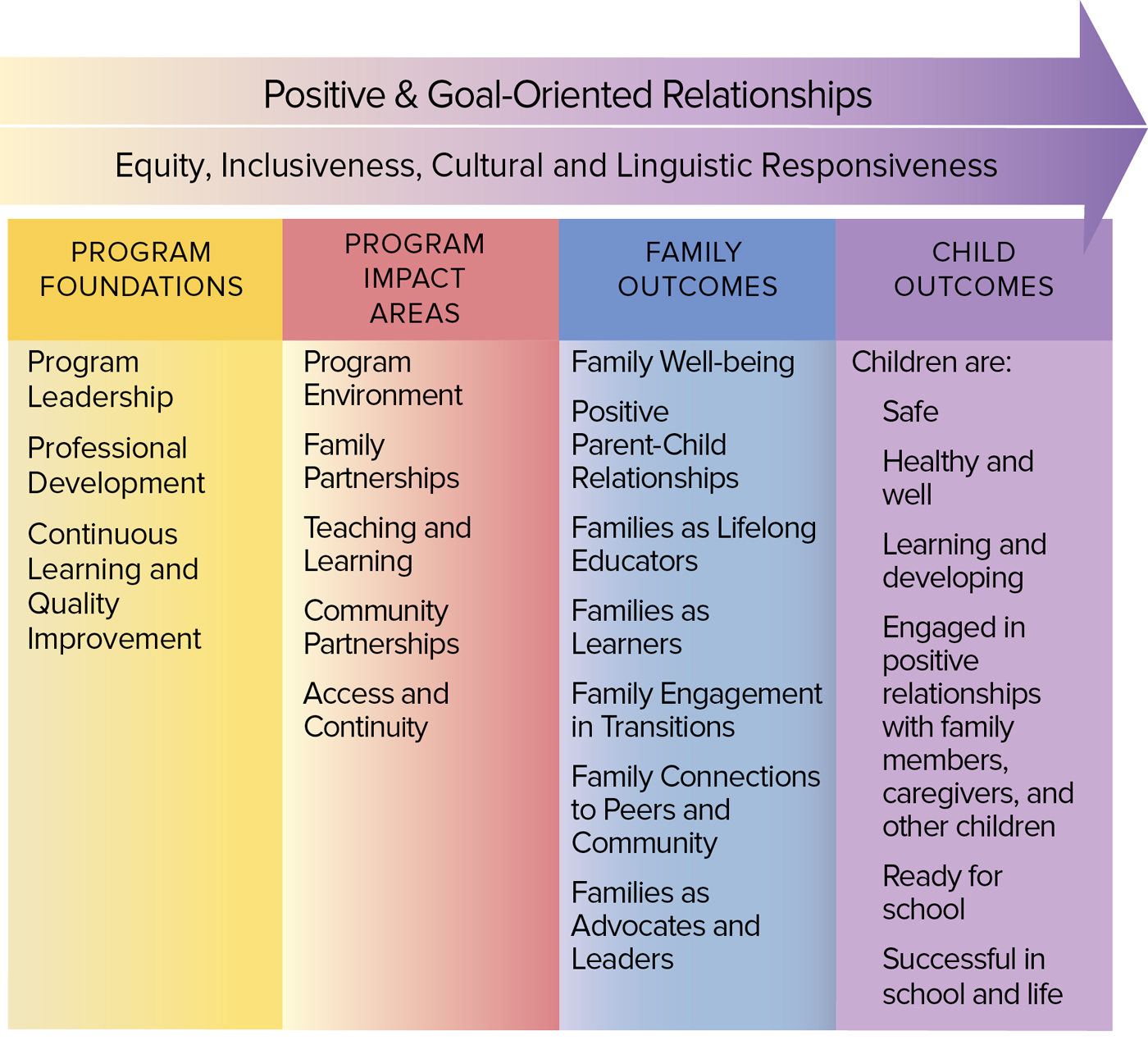

The Office of Head Start Parent, Family, and Community Engagement (PFCE) Framework is a road map for progress. It is a research-based approach to program change designed to help Head Start programs achieve outcomes that lead to positive and enduring change for children and families. When parent and family engagement activities are systemic and integrated across PFCE Framework Program Foundations and Program Impact Areas, better family outcomes are achieved. This leads to children who are healthy and ready for school. Parent and family engagement activities are grounded in positive, ongoing, and goal-oriented relationships with families.

What Are Positive Goal-Oriented Relationships?

The goal of parent and family engagement is to build strong and effective partnerships with families that can help children and families thrive. These partnerships are grounded in positive, ongoing, and goal-oriented relationships with families. Positive Goal-Oriented Relationships are based on mutual respect and trust and are developed over time, through a series of interactions between staff and families. Successful relationships focus on families’ strengths and a shared commitment to the child’s well-being and success. As relationships between staff and families are strengthened, mutually respectful partnerships are built. Strong partnerships with families contribute to positive and lasting change for families and children.

Why Do Positive Goal-Oriented Relationships Matter?

Positive Goal-Oriented Relationships support progress for children and families. These relationships contribute to positive parent-child relationships, a key predictor for success in children’s early learning and healthy development. Through positive interactions with their most important caregivers, children develop skills for success in school and life. They learn how to manage their emotions and behaviors, solve problems, adjust to new situations, resolve conflicts, and prepare for healthy relationships with adults and peers.

Healthy relationships between parents and children develop through a series of interactions over time. Healthy relationships are primarily built on warm, positive interactions. There may also be brief disconnections or misunderstandings in relationships. For example, there will be times when parents and children are not perfectly in sync. A toddler may be laughing and playing with a parent and then be surprised when her scream of delight is met with her mother’s raised voice, telling her to be quieter. An older infant is enjoying his breakfast of rice cereal and is confronted by an unhappy face when he smashes the oatmeal into his grandmother’s work clothes. These temporary disconnections are natural and necessary, and they build a child’s capacity for resilience and conflict resolution. As long as interactions are primarily positive, children can learn important skills from the process of reconnecting.

Disconnections and challenges can occur in our relationships with families and colleagues as well. A father arrives to find his daughter happily splashing in rain puddles and is upset with the caregiver. He is in a hurry and doesn’t have time to change her clothes. A mother is frustrated that her child is not making more progress and blames the caregivers. Imperfect interactions help us learn how to tolerate discomfort and how to resolve challenges. These are important skills for building strong partnerships.

Positive relationships between parents and providers are important as families make progress toward other goals, such as improved health and safety, increased financial stability, and enhanced leadership skills. Strong partnerships can provide a safe place where families may explore their hopes, share their challenges, and let us know how we can help. Staff, community partners, and peers can be resources as families decide what is important to them and how to make it happen. Parents help us learn how to enhance their children’s learning and healthy development. When we focus on families’ strengths and view parents as partners, we can work more effectively to support parent-child relationships and other outcomes for families and children.

Everything we do is intended to give families the emotional and concrete supports they want and need to reach better outcomes. When a family makes progress, parents have more capacity to give to their children. For example, a family may be struggling financially and constantly worried about where their next meal will come from. The parent may be overwhelmed or embarrassed, unsure of how to ask for help. If the parent trusts the program or a staff member, the parent might share their distress and worry. The program can work with the parent to find and access food and nutrition resources in their community. As the family stabilizes, the parent might work with staff to identify how to improve the situation in the long term. The parent may decide to go back to school to increase his or her earning potential or might join a group to talk with other families about educational goals. The parent might work with the program and peers to find and access educational resource. As families take steps to reach their goals, they can engage in relationships with their children that prepare children for success and in life.

Recognizing What Families, Staff, and Children Contribute

Building a relationship is a dynamic and ongoing process that depends on contributions from families, program staff, and children. Families have a set of beliefs, attitudes, and perspectives that affect relationships with staff. Likewise, we as providers have a set of beliefs, attitudes, and perspectives, both personal and professional, which affect our relationships with families. Children also bring unique contributions to relationships. They live and learn in a unique environment and are influenced by their parents, families, and other adults and peers in their lives. Children bring their behavior, temperament, emotion, and developmental stage to their interactions with family members and staff.

Understanding and Appreciating Differences

Successful partnerships are created when families and staff value the perspective and contributions of one another and care about a shared goal and positive outcome. Programs can partner with parents to understand the child's and family's strengths, goals, interests and challenges. In each interaction we can learn more about each other and about ourselves as professionals. When we understand and appreciate the perspective of the family, we are more likely to create successful partnerships. We let go of our own agenda and create a shared agenda with the family. We often refer to this as "meeting families where they are."

Meeting Families Where They Are: Cultural Perspectives

Understanding cultural beliefs and priorities is key to building relationships with families and is part of meeting families where they are. Each family comes to Head Start programs with unique cultures that give meaning and direction to their lives. Culture is complex and is influenced by family traditions, country of origin, ethnic identity, cultural group, community norms, experiences, and home language. Cultural beliefs of individual family members and the entire family affect caregiving behaviors and inform decisions made about the child and the family. Culture affects our views on key issues such as education, family roles, childrearing practices, what constitutes school readiness, and how children should behave. Reflecting on the family’s perspectives and learning more about them can help us think about how their cultural beliefs and values influence their choices and goals. In addition, we need to fully understand our own perspective and how our own experiences, biases, and cultures affect our perspective.

The ways that cultural beliefs affect relationship building can be obvious or subtle. Regardless, cultural perspectives inform the choices families and professionals make. Some examples of the decisions and child-rearing practices that can be influenced by culture are:

- Communication. How do the parents want their child to address a teacher, grandparent, doctor, or neighbor? Is saying ‘hello’ important when meeting someone new? Is eye contact a sign of respect or disrespect?

- Role of Professionals. Is it acceptable to disagree with their child’s teacher? Are there areas of development and behavior that are seen as solely the responsibility of the professionals? Of the family?

- Caregiving (Sleeping, Eating, Toileting). Will a child sleep alone or with her parents? Will she be breast-fed or bottle-fed when she is an infant? Will she be expected to use a spoon to eat her food or will she be encouraged to eat with her hands? When will she be expected to start using the toilet?

- Discipline. How will he be disciplined if he is in danger? What if he bites a friend? What if he throws a temper tantrum at the park? Are there specific discipline strategies that parents think are more or less effective?

- Language. Is there a home language that is important to the family? Do they want her to only speak English at school and speak the home language with family? Are there important cultural traditions that rely on an understanding of a home language?

- Learning. Does the family see themselves as important teachers or is learning something that teachers are responsible for? What kind of activities does the family like to do at home? Is there a certain age when the family expects him to be reading? Where does a child learn?

Culture is real and important, but understanding it is not necessarily simple or easy. It takes patience, commitment, and a willingness to feel uncomfortable at times. It also takes courage and humility to look at our assumptions and biases and see how they affect our attitudes towards families. Our goals, insights, and experiences guide the choices we make as we build our relationships. Leadership and staff can make this a priority by dedicating professional development activities, including reflective practice and reflective supervision, to understanding how culture and language affects partnerships with families. Everyone benefits when we learn from families and bring new ideas and skills to our work.

Respectful partnerships are created when families and staff care about shared and positive outcomes, and value the perspective and contributions of one another.

Read more:

Resource Type: Article

National Centers: Parent, Family and Community Engagement

Audience: Family Service Workers

Last Updated: February 19, 2025